Recently, when we were spreading the word about our online talk ‘Mapping the Táin’ by Paul Gosling on social media, we used a painting by artist and farmer Joe Ryder, Donegal, from a series of his artworks inspired by Cú Chulainn and the Táin. This generated a great reaction so we decided that we’d like to find out more about Joe’s work on Irish legends and mythology and the inspiration behind them.

Joe grew up in Lurgan, Co. Armagh. His father, from Ardboe, Co Tyrone, was a school principal in Killwarlin near Moira, Co Down. Because Joe’s mother worked outside the home, Joe at a young age would accompany his father to school. As he sat in his father’s class, he’d listen to him teach the pupils about the heroics of Setanta and the Táin, and so the seed was sown.

Later, when Joe was a pupil in his own right at St Peter’s, Lurgan, his teacher, Michael McAliskey (husband of Bernadette Devlin, the civil rights leader and politician) nurtured that seed. There was a book about Cú Chulainn in the class, but only the one copy, and the teacher would pass around the book to each boy in turn, making them stand up and read a portion of the Táin. The teacher was strict, and Joe recalls that if you didn’t pay attention, you would soon feel the force of a flying blackboard duster at the back of your head, or a whack on the paw from the dreaded strap. But most of the time, it wasn’t needed, as the boys loved those hours spent reading the Táin. When the teacher came in and announced ‘Cú Chulainn today!’ a whoop of joy would go up from the boys. For them, it was an escape, ‘the great escape’ as Joe said from the ‘stuff’ that was going on at the time in Northern Ireland. Off to get lost in the land of legends.

Joe’s grandparents lived in Tullydonnel, South Armagh, and he would stay there on his summer holidays. Joe would spend many of his days on the dairy farm of John Smith in Ballsmill. Through the day-to-day business of farming, they travelled extensively around the area of the Ring of Gullion, Joe sometimes sitting on the mudguard of John’s Fordson Major tractor, or up in the cab of his Bedford Tipper lorry. They would draw straw from Ardee on a Commer flat bed, 9 rows high, or draw brewer’s grains in the Bedford Tipper from the Harp factory in Dundalk, Slieve Gullion and the Cooley mountains a constant backdrop.

Joe cites the day they were drawing brewer’s grain from Dundalk up to Ballsmill and were coming back by the backroads to avoid the checkpoints because of the old Bedford’s mechanics. It had to be started namely on the slope (Joe remembers vividly how the brakes were pumped with a bit of blue twine up and over the steering wheel). John stopped the lorry and told Joe to get out and look over the hedge. On returning to the cab and looking puzzled, John informed him that was the glen where the Brown Bull and heifers where hidden. Joe was astonished at this revelation: ‘How the blazes do you know that?!’ John told him that he had learnt about The Táin at his father’s knee and his father same before him. He would have heard of it at ceilidh houses from story tellers and travelling Seanchaí. Indeed, there is a rich culture of the oral tradition in that whole area and nurtured and encouraged in the youth today. It was at that moment when the strands of the Táin that he had heard or read came together and ingrained in him a huge love for the people, places and stories.

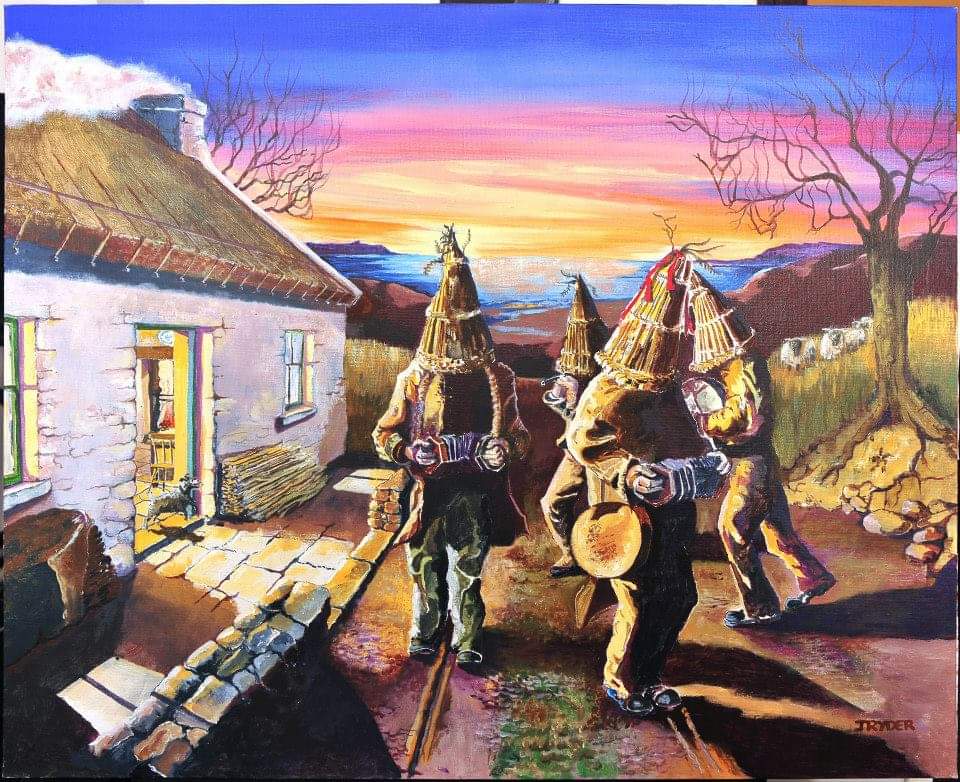

Similarly, Joe’s Mother was an influence on him. She grew up in the area having been evacuated as a child from Belfast during the Blitz, eventually the whole family residing there. Joe speaks of her knowledge of the Táin and about her hearing the stories, like his father, at ceilidh houses (known as ‘rambling houses’ in Donegal) as far as Mullaghbawn; and her seeing and hearing the Mummers as a child (which were to be an inspiration for Joe’s painting ‘Mummers on the Mountain’); and how, depending on the persuasion of the household they visited, they’d either perform ‘King George’ or ‘St Patrick’. The parents wouldn’t tell the children that the Mummers were coming in order to keep the element of surprise and as Joe notes, the Mummers would ‘scare the bejaysus’ out of the children when they entered the room.

Looking at this Armagh man’s paintings online, the themes that emerge are of Cú Chulainn and the Táin, cattle and sheep, and the sea. And it all reminds me of here, Cooley, and I think how this man rightly has a sense of belonging to this area.