The Vikings had one or more settlements on Carlingford Lough, but we don’t really know if it was at Carlingford, some of the annals indicate Narrow water. We don’t know if it was named after a Viking called Carlin, although the name does sound vaguely Scandinavian.

We certainly don’t know what they looked like, although one thing we do know with a high degree of certainty, is that they didn’t have helmets with horns on them. There are no horns in the image above, from an English illuminated manuscript. There are thousands of accounts in the Irish annals – a simple list of them runs to 25 pages – without a mention of horns. The whole horns business can in fact be traced to the staging of Richard Wagner operas in the 19th century.

The term Viking comes from Scandinavian words for ‘bay’ – ‘vig’ in Danish or Norwegian, ‘vik’ in Swedish. It was a sort of nickname for the people who lived along the shore who were mostly fishermen and fisherwomen (gender equality goes a long way back, there were women on raiding parties).

Some historians believe they went raiding because they had over-fished the herring stocks in the North Sea. They first appeared in Ireland in 795, raiding a monastery on Lambay Island. For at least half a century they were purely seasonal raiders and did not establish settlements for over-wintering.

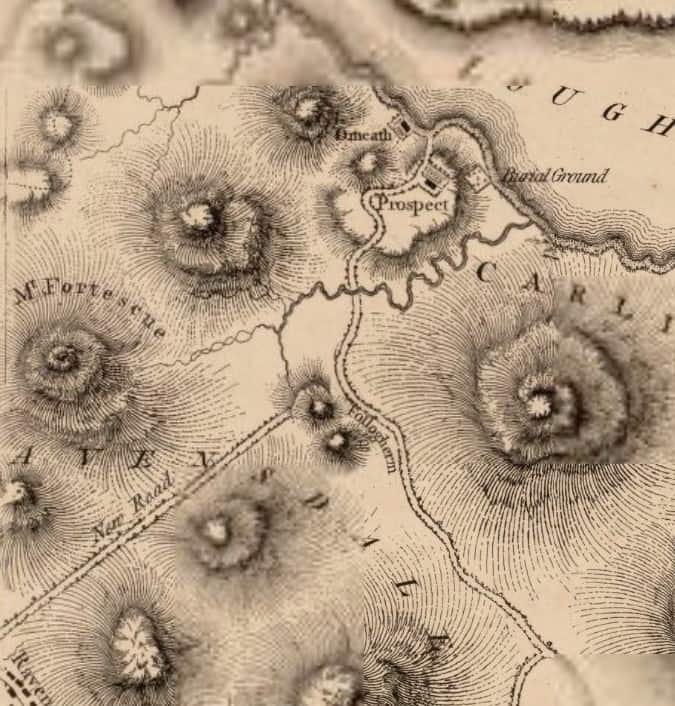

In the early 800s, they raided the monastery at Killeavy (Old Church), a place they returned to at regular intervals for more than a century. The monks got sick of it, so in the spring they would put a lookout on a hill overlooking Carlingford Lough. If he saw sails below he would run a warning flag up a great flagpole on the hill.

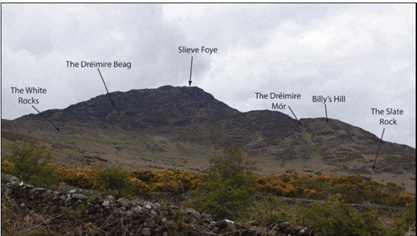

From Flagstaff, you can see the whole lough. Then look west towards Slieve Gullion and on a clear day, you can see the white statue at St Monnina’s well, above the monastery site – so the monks could easily see the flag.

The Vikings were the most expert seamen (and women) of their age and many words to do with boats have come into English and Irish. Their longboats had a rounded stern so the tiller was fixed on the side of the boat, the right-hand side. It was a long, slender piece of wood used to steer the boat which they called the ‘starboard’ (steering board, pronounced ‘stoorbord’), which gave us starboard. The man in charge of the skib (ship) was called the ‘skibber’ but we say, skipper.

The Vikings had pigs in their boats for food: somewhere in the annals, a monk wrote that even worse than the killing and ransacking was the smell of pigs that they left behind them. But generally, historians believe that their personal hygiene was a step or two above what prevailed in England and Ireland at the time.

They left their trade in the landscape too in the form of place names. In England, the ending of Norwich is just a variation on ‘vig’ or ‘vik, everyplace ending in-by, (Ingoldsby), was a Viking village or ‘by’, (pronounced roughly boo), and some had ‘bylov’ or bye-laws.

Howth was originally ‘hoved’ which is the modern Danish word for head. Closer to home we have Greenore and I am prepared to bet the farm it comes from ‘grønør’ (pronounced groonoor), a green shingle or sandbank. Throughout Scandinavia there are coastal place-names ending in ‘-ør’ (such as Elsinore or Helsingør in Denmark where Hamlet’s Castle stands), all involving shingle or sandbanks.

Wagner wrote a tragic opera about the love story of Tristan and Isolde, (sometimes spelt Iseult). There is a theory that Iseult, (if she existed), was the daughter of a Viking chieftain who lived in Omeath, but that, as they say, is another story.